|

||||||||||

| Dyed and Gone to Heaven – An Online Magazine and Needlework Resource |

|

||||||||||||

|

|

Needlework, Knots and Other Crafts on the High Seas

By Rita Vainius

Needlework, engaged in as a pastime by sailors on their long sea voyages, is not as farfetched a concept as one might imagine. There is an account of a particularly burly naval officer, a champion swimmer and well known rugby player, whose relaxation was knitting, which he did supremely well. Another sailor, incapacitated by falling from the mast of his ship, turned his idle hands to the practice of embroidery with great dexterity, producing an altar cloth. This needleart is clearly the work of a sailor, judging by subject and sentiment. Also, it was executed on a "silk"- the black kerchief worn by a seaman, previously bound upon his head.

A favorite pastime for sailors when they got together was to swap "tall tales" and compare skills. A common well-worn phrase of nautical origin comes to mind. In making spun yarn from untwisted yarns of rope, it took two men to operate the winch. Working together in a sheltered spot, the pair enlivened their task with conversation. Hence the expression: "to spin a yarn or twister". For those who are staunch fans of the writings of Herman Melville, Patrick O'Brien and other period nautical literature, there are numerous references in these sea tales to sailors engaged in "fancywork", as all these ornamental fiber crafts were collectively named.

Sailors drilled shells and threaded them to create mats similar to how beads are often used in needlework today.

Perhaps the most unique and fascinating of all sailors' needlework and a subject about which little has been written is "wool pictures". Nostalgia for the days of sail seems to have played a major role in the choice of subject matter. The pictures were worked in crewel consisting of long and short stitches. The backing was sailcloth, the stitching most often wool, but occasionally also silk, with the rigging done in cotton and linen threads. The technique of working these pictures was to set up the canvas and ink in the outlines of the ship before commencing with needle and thread. The sea, sky and other details were likely stitched in freehand since pieces give evidence of this in the charming liberties taken with the appearance of these elements The names of the ships were most often shown, but seldom was the name of the artist included. The great majority seem to have been completed in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, when was quite a craze for wool pictures, a period when a fad for "Berlin Woolwork" spread through both Europe and America.

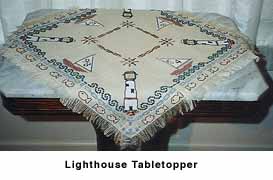

Nautical Themes are popular in needlepoint as shown in these examples by this month's featured designer Claudia Dutcher

The whole spirit and style of these yarn pictures is amateur folk art and sailorly attention is paid to the rigging, which in good examples is fashioned from several different thicknesses of threads, as dictated by the rope's original usage. It has been proposed that these "wool pictures" were an example of "occupational therapy" at the Sailors' Hospital in Greenwich, England. In World War I, the wounded were provided with perforated cards, blunt needles and a supply of wool so that they might stitch patriotic motifs such as the flags of the Allies. Another theory holds that the inspiration for wool pictures came from the Chinese embroideries sold to sailors in Hong Kong and the Treaty Ports, opened to the west in 1842. Regardless of their origins, examples of these wool pictures are prized collectors' items and they are objects of considerable charm and interest.

Both vegetable and animal fibers, spun or woven, have been put to use by sailors. The seafaring man had to ply his own needle, in the absence of female assistance, and it is not too great a step from darning socks to engaging in other types of needlework. The simplest and easiest thing for a motivated sailor to do would be to decorate the tools of his trade. If inspired still further there were wool pictures, embroidery or wilder flights of fancy knotting to be explored.

Traditionally sailors had few entertainment diversions at sea except for some musical instruments. While the vast majority of sailors off-duty would be content to chew their "quid of baccy" and rest their tired limbs, others took up some handicraft. A "down-to-earth" art developed at sea, among the simplest and poorest of men, whose only skill, aside from personal survival, lay in their hands and the use of shipboard material. The techniques employed in maintaining the ship's gear were used, modified and adapted in countless variations for making and decorating personal items such as knives, telescopes, needle cases, work baskets, sewing boxes and sea chests. As illiterate and inarticulate as a sailor may have been until fairly recent times, he often had a sure eye and a steady touch while quietly at work on the watch below.

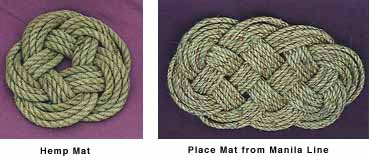

Perhaps nowhere in the maritime world do function and art meld more completely than in knot art. Like so much of maritime lore, knot making has been a cumulative development over millennia and almost every use to which a piece of rope can conceivably be put has its attendant knot, splice or stitch that centuries of use have indicated is most suited to the task. Sailors devoted much of their leisure time to contriving many beautiful and ornamental knot designs. Most of the knowledge on this subject was never published, but handed down man to man, and generation to generation.

Sailors often engaged in a special type of knotting worked with a number of cords suspended from a bar or a line. This type of knotwork was known as macrame. It can also be formed from a fringe of cords combed from the cut edge of a woven material. The origin of the word, macrame, may be traced to Turkey in the 13th century, when hand towels were knotted and fringed in this manner and called "makrama" from the old Arabic. It was already an established art in France in the 14th century and throughout the reign of Queen Victoria, cultured ladies found it to be an agreeable pastime.

Simplicity of execution, requiring a minimum of skill, materials and space to be practiced, brought macrame into instant favor with seafaring men. By the 15th century they were using items made with macrame to barter with the natives of India and China and later with the North American Indians. It is considered by many art and craft experts to be unsurpassed as a diversionary form of activity which develops originality and initiative while providing recreational exercise.

Aside from the functional aspect of knotwork, there is a good deal of aesthetic pleasure to be found in its application. The sailor could easily hold up his pants with a bit of twine, yet he spends hours fashioning a macrame belt from multiple strands, containing a dozen different patterns and colors; a mat is carefully woven and placed at the entrance to the companionway, when a few strips of rope would suffice; the entire interior of the admiral's barge and the captain's gig are, even today, sometimes completely covered with a kind of seagoing "lace"- fancy knotwork that took months to complete; the bosun hangs his "call" around his neck, not by a piece of cord, but by a sennet, (a plait or braid), encased in the whistle knot. The fact that this knot and sennet are invariably associated with this peculiar whistle, would indicate a strong sense of ritualism - one of the earliest aspects of art.

Most of the old knots have a clear elemental beauty, which is often found in utilitarian objects whose shape has been refined by evolution to produce the best results from the simplest form. These ancient knots provide a fascinating, useful and inexpensive hobby, but are virtually unknown to many experts and teachers of other crafts that have developed from them, such as basketwork, weaving, crochet and macrame. Avid current day needleworkers and designers who favor a particular technique such as needlepoint, counted cross stitch, crewel etc. quite often discovered their interest in handiwork at a young age. Frequently, these preferences for a particular technique or method of self-expression were the outcome of much experimentation with other types of fiber crafts along the way, usually including macrame, weaving or crocheting, all derivatives of simple knotwork techniques.What else did these sea-going "fiber artists" create on board? They made handles for implements and chests, life preservers, blackjacks, handcuffs, needle cases, rope ladders, serving trays, bell pulls, decorative chains, lanyards, bracelets, cuff-links, shoes, moccasins and sandals, hats, quirts, table and floor mats, rugs, handbags, purses, necklaces, sashes, epaulets, belts, baskets, bottle and jar covers, even picture frames and an almost limitless supply of buttons and toggles. The artist in each craftsman dictated that he experiment with different combinations of forms, fibers and colors. To him, the art of his creation lay in the marriage of different techniques and shapes into a harmonious whole. The more difficult the feat - the greater the art.

One of the best uses of fancywork was to provide handsome coverings for plain or even downright ugly objects thereby giving them a different look and a new life. Empty jars and pots could be converted into unique containers; bottles and flasks offered a wide range of styles for conversion. Even the caps and covers for these often sported Turk's head or crowned star knots.

The two arts that belong almost exclusively to the sailor are scrimshaw, (carved etching on the jawbone or teeth of sharks and whales), which was particular to whaling, and knotting which belonged to all deep water ships. Of all the sailors' arts, it was knotmaking in it's various guises and permutations that excelled in technical finesse and exceeded all other nautical arts in both quality and variety. Many of these remaining artifacts are interesting both as a record of things past and as authentic folk art.

Even though the halcyon days of knotwork disappeared with the advent of steam in place of sails, knowledge of marlinspike seamanship, as it is also called, still distinguishes to this day the true seaman from the man who merely ventures upon the water. No one can become a skipper or should aspire to distinction who has not mastered knots, needlework and the making of small objects on board as necessary.

The nautical theme has, in a way, come full circle from the sailors of yore who through their ingenuity created objects of practical use and consummate beauty with the barest of materials, which then evolved into other crafts that have survived the intervening years. Though the practice of many original seagoing crafts has all but disappeared, there are artisans who have kept some of this handiwork alive on land and perhaps the future will bring a resurgence of interest in others. One related aspect which is very much in evidence is the continuous and ever growing popularity of nautical motifs for needlework of all kinds: anchors, sailing ships, lighthouses, compass headings and rope shaped border designs abound as you will witness in our other nautically themed features.

The Ropewalk

In that building, long and low,

With its windows all in a-row,

like the port-holes of a hulk,

Human spiders spin and spin,

Backward down their threads so thin

Dropping, each a hempen bulk..

...Ships rejoicing in the breeze,

Wrecks that float o'er unknown seas,

Anchors dragged through faithless sand;

Sea-fog drifting overhead,

And, with lessening line and lead,

Sailors feeling for the land.

All these scenes do I behold,

These, and many left untold,

In that building long and low;

While the wheel goes round and round,

With a drowsy, dreamy sound,

And the spinners backward go.Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Credits: All knotwork examples are from the private collection of Captian David Berson, sailor, writer, teacher of celestial navigation and musician and entertainer for charters on the ship "Pioneer" at the South Street Seaport in NYC. For further information you can contact him at: (516) 477-2435.

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: No part of this feature story nor the included designs/charts can be reproduced or distributed in any form (including electronic) or used as a teaching tool without the prior written permission of the CARON Collection Ltd. or the featured designers. One time reproduction privileges provided to our web site visitors for and limited to personal use only.

© 1997 The Caron Collection / Voice: (203) 381-9999, Fax: 203 381-9003