In the early 1900's linen was becoming scarce and an alternative

fabric was needed. Cotton had become more readily available and

soon supplanted the use of linen. Cotton sultan grew in popularity

and came to be specifically known as Hardanger fabric. Colors

were also introduced, resulting in a contemporary adaptation

of this venerable old textile art. More recently, Hardanger canvas

manufactured especially for this purpose came to be used, but

some sizes of scrim and congress canvas and many dress materials

were also adapted to suit the work. Since linen was scarce, it

was often used to make only the accents on a garment, such as

collars, front tabs and cuffs on a blouse or shirt or as an insert

for an apron. Household linens were stitched almost exclusively

on cotton sultan.

A new trend took hold in the early part of the twentieth century,

of adding surface embroidery to Hardanger work. The two principal

stitches used were satin or kloster stitch for the solid portions

of the design and over and under woven bars for the drawn spaces.

Satin stitch variations, eyelets, back stitch, fagot and reverse

fagot, four sided stitch and kloster block variations embellished

with luxurious lace filling stitches were integrated with them.

Open areas were also embellished with double and diagonal bars,

dove's eye and spider web stitches. Picots could be added to

woven bars while weaving. Norwegian picots were tight little

knots. Today picots are more often small lacy loops.

The mid 1800's to the early 1900's saw a huge tide of immigration

from the Scandinavian countries to the U.S. and with them came

their native embroidery skills and techniques. Before this mass

transplantation Hardanger was a relatively obscure and isolated

embroidery technique. The "Ladies Home Journal", May,

1901 issue, published the first introduction to Hardanger in

America, written by the editor of The Lace Maker, Sara

Hadley. This article and several subsequent others on the subject

were later consolidated and published as The Complete Hardanger

Book in 1904 and as Supplementary Lessons in Hardanger in 1906, both put out by D.S. Bennett. There followed more books

by T. Buettner and Co., Butterick, DMC, Belding and Priscilla.

For those who wish to investigate a period publication on Hardanger,

Dover Books currently stocks Hardanger Embroidery by Sigrid

Bright which is a reprint of the Clark ONT J. Coats Priscilla

book of 1909. Part of this book was also reprinted by Tower Press

in 1981 as the Hardanger Book.

During and after the period of the two World Wars, much of this

embroidery diminished in use and faded from sight. The publication

of Jean Kimmond's Embroidery for the Home and a J.P. Coats

publication helped generate a resurgence of interest in Hardanger.

Since the 1970's, this spark has grown by leaps and bounds due

to the publication of numerous books and leaflets and through

the efforts and work of Marion Scoular, Rita Tubbs, Evelyn MacKay,

Janice Love, Elvia Quinn, Gayle Hillert and Alphea Iverson. This

revival has spurred classes and correspondence courses, the publication

of a newsletter and even an annual contest for Hardanger enthusiasts,

sponsored by Nordic Needle of Fargo, ND.

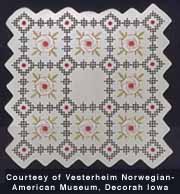

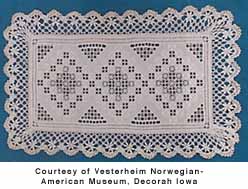

Another superb resource for this art form is Vesterheim (Western

Home) Norwegian-American Museum, which is tucked away in the

small town of Decorah in northeast Iowa. This Norwegian- American

institution is one of the outstanding ethnic museums of America,

specializing in the preservation of Norwegian-American art, crafts,

artifacts, tools and architecture, telling the story of Norwegian

immigrants, encompassing their home and life in Norway, their

journey to America and their adaptation to a new home in the

Midwestern part of this country. In the U.S., the women from

Norway created some of the loveliest Hardanger embroideries in

the world. The textile area of the museum exhibits a bunad (festive

folk costume) for almost every part of Norway, as well as examples

of weaving, tatting, blackwork, crocheting, knitting, rosesaum

(rosework), and hvitsom (whitework, of which Hardanger embroidery

is a part). The bunads from different parts of Norway can vary

greatly in style. The typical Hardanger, or west coast costume,

consists of an apron (often with an embroidered panel), long

sleeved blouse of white linen with embroidered collar and cuffs,

long black wool skirt and a red woolen sleeveless bodice. The

bunads of the Hardanger district are the only ones with this

now famous, embroidery technique. The examples of Hardangersom

at Vesterheim encompass a collection of works dating from the

late 1700's to the present as well as several trousseaus, spanning

from 1880 to the early 1920's.

There is some controversy regarding some of the embroidery which

is given the appellation of Hardanger. What began as a decoration

for household linens has been turned into something else which

purists refer to as "American Hardanger." This would

include any work which employs colors other than white or cream

or is executed on cotton rather than linen cloth. Applications

for these contemporary "American Hardanger" embroideries

have grown to encompass tablecloths, doilies, runners, wallhangings,

pillows, bedspreads, baptismal and wedding gown trims, bookmarks,

Christmas ornaments, bellpulls, sun catchers, liturgical vestments,

needle cases, pincushions, coasters, bread covers and even doll

clothes. However, even though the designs, applications and materials

have multiplied since the 18th century, the basic techniques

remain the same. White-on-white remains the most traditional

and, for many, the most elegant choice for Hardanger embroidery.

Traditionalists can continue to work Hardanger in its original

pure form, while those who are more experimentally inclined can

employ the numerous new choices of materials now available.

Thanks to places like Vesterheim Norwegian American Museum, which

preserve the traditional embroidery examples and techniques which

the immigrants transplanted to the New World, and to talented

designers, who have combined original stitches and techniques

with new fabrics, threads, colors and embellishments, to add

a contemporary, vibrant flair to Hardanger embroidery, that compel

enthusiastic new stitchers to take up this art, Hardangersom

has enjoyed a renaissance and is once more a vital and popular

form of needleart.

For more information on Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum located at 523 W. Water Street, P.O. Box 379, Decorah, Iowa,

52101-0379, please call them at (319) 382-9681 or visit their

website at http://www.vesterheim.org

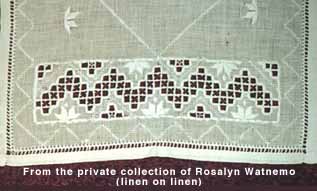

Information for this story was gathered from many sources, most

notably The Hardangersom of Vesterheim Vol. II by Carolynn

Craig Gustafson, which is available from Nordic Needle. Special

thanks also to Vicki McEntaffer of Kunsten Needle Art, Roz Watnemo of Nordic Needle and Laurann Gilbertson,

curator of textiles at Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum,

for generously sharing their time, knowledge and related materials

concerning the history of Hardanger embroidery.

For more information on Rosalyn Watnemo and Nordic

Needle see this month's Designer Spotlight and Shop Focus. Nordic Needle has some vintage Hardanger table

and bed linens for sale, which can be viewed on their website

at http://www.nordicneedle.com/antique.htm

For more information on Vicki McEntaffer, Kunsten Needle Art, Lillill Thuve or Thuve-Stua designs see last month's Innovation Gallery Feature.

For those interested in other Norwegian cultural events, please

see the Sons of Norway website at http://www.sofn-district6.com